Entschëllegt, dëse Guide ass nëmmen op Englesch verfügbar.

Guide on how to do public history in urban spaces

Based on concrete examples drawn from the Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (C²DH)’s activities in the city of Esch sur Alzette (Luxembourg) between 2020 and 2024, this guide offers a method to develop more collaborative public projects on the history of cities, towns, neighborhoods, with local communities. Public history is a way of producing a history that is more accessible to the general public, that relies on the participation from members of the public, and that engages with public debates about the past. The co-creation of history between researchers, institutions, associations, and local residents supports public and social inclusion, and provides participants with training and new understanding of their city, neighborhood, and community. Designed as a WikiHow, this guide proposes several how-to steps.

In the spirit of co-creation

Thomas Cauvin and Joëlla van Donkersgoed compiled that Guide as part of a FNR ATTRACT Grant. We have opened up this guide for your suggestions using a Hypothesis plug-in. You can highlight and leave your comments and suggestions using the tools in the top-right corner.

Step 1: How to start a public history project?

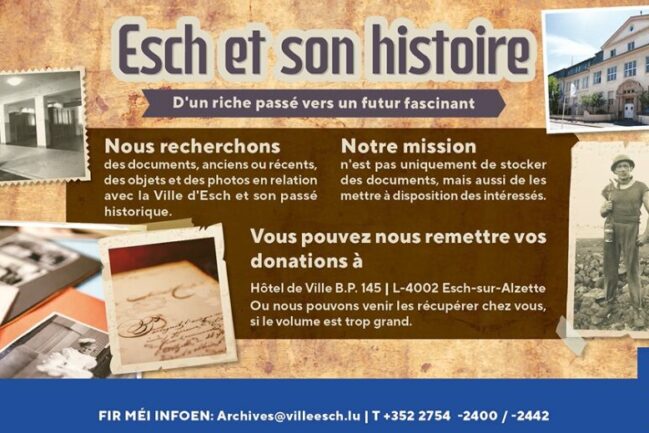

Each initiative requires a leading institution, association or individual to launch the process. The initial idea may come from a cultural (for instance the Archives of Esch sur Alzette, fig. 1) a research institution, a group, association or community, or any individual interested in local history.

Collaboration is key. It is recommended that projects be based on a collaboration between several partners, groups, and individuals. Collaboration allows and supports more inclusive and diverse frameworks of history production. For instance, for the HistorEsch and FL’ESCH Back projects, researchers from the C²DH worked closely with la Nuit de la Culture (a municipal organization), the KulturFabrik, and dozens of local residents.

Step 2: How to frame a project?

Find a historical topic that resonates in the present. The organizing team needs to identify and propose a historical topic for the project. The topic could be the general history of the town – like HistorEsch did for the city of Esch sur Alzette – of a neighborhood – as we did for the Lallange neighborhood in Esch sur Alzette, fig. 2 – of a street or any other identified space. Popular topics may also include local events, characters, or traditions. The general public can express specific interest in some historical topics for the project.

Develop a format that is accessible to the general public. The format can take many shapes, sometimes a physical installation such as a mural (fig. 2), or digital such as an App (for instance Minett Stories). In either case, contents should be clear and comprehensible to the general public. Visual and sound contents help develop interaction between the public and the history. In the Lovó project (about the history of Esch from the perspective of Portuguese speaking grand-mothers), historical testimonies are presented and communicated through sound and visual installations in the streets of the city.

Find a place which is welcoming to your target audience. Public accessibility to the site of the project is crucial. We suggest choosing public, open, and free of charge sites to support public access. For our history of Esch sur Alzette in 25 objects, we installed the exhibition in a “pop-up store” in the main shopping street of the city.

Step 3: How to ensure the quality of the historical project?

The team should design a framework to insure the quality of the historical content of the project. In order to frame the historical topic, the team can compile information (publications, online resources) and past projects. This can also lead to the production of a short summary of the historical topic that can be shared with participants.

This summary can be driven by questions to better understand the historical topic. Much more than a simple list of dates, the team should look at explaining to a large audience what the topic is about, why its history matters, its impacts and connections to the present. The summary can also briefly identify themes, main events, sites, or characters, associated with the topic of the project. This will provide the historical context to situate the contributions from the public. For instance, a CHiC (fig. 3) – Citizen Historian Circle – was formed for HistorEsch. Composed of local residents and researchers, the CHiC contributed to contextualizing the history of the Lallange neighborhood and identify major changes through which the town went through since the 1960s. In this session, the CHiC proposed specific keywords to frame the history of Esch sur Alzette. The team could make the summary accessible (also online so that participants can contribute and enrich the summary) to participants and use it to identify knowledgeable people (researchers, local historians, archivists, members of associations) who can help to frame the history of the topic.

Develop a format that is accessible to the general public. The format can take many shapes, sometimes a physical installation such as a mural (fig. 2), or digital such as an App (for instance Minett Stories). In either case, contents should be clear and comprehensible to the general public. Visual and sound contents help develop interaction between the public and the history. In the Lovó project (about the history of Esch from the perspective of Portuguese speaking grand-mothers), historical testimonies are presented and communicated through sound and visual installations in the streets of the city.

Find a place which is welcoming to your target audience. Public accessibility to the site of the project is crucial. We suggest choosing public, open, and free of charge sites to support public access. For our history of Esch sur Alzette in 25 objects, we installed the exhibition in a “pop-up store” in the main shopping street of the city.

Step 4: How to collect data with and from the public?

Creating a simple and accessible way for the public to contribute to your project is paramount to co-creation. The method of engagement can range from forms of crowdsourcing (online collecting of photographs for instance), or by organizing public workshops where people bring objects, documents, family heirlooms, and/or provide testimonies. The type of objects, documents, or testimonies to be collected depends on the objectives, framework, and type of final production of the projects.

Hybrid (online and on site) collecting offers a broad range of opportunities. Choosing one method, such online crowdsourcing, might exclude those who are not digitally proficient. Therefore, a hybrid approach using both in-person and online methods to harvest public input could reach more people. Fig. 4 shows members of the public bringing documents, letters, photographs during an event organised in a public library. To ensure a sustainable hub to organize both in-person and online collection, the C²DH has created Historesch Gesinn. On this platform new historical research is announced, events are promoted, and people can contribute their personal documents to ongoing historical projects.

The leading institution should oversee the structure of the project, safeguard the data and maintain the project goals and accessibility. Incorporating a person or a committee who will ensure the accuracy of the project output is crucial. When conducting a project, make sure that the collected data is stored and shared in a way that ensures the privacy rights of the participants through consent forms and a secured storage facility. Documents might be simply borrowed and returned to owners after the end of the project. For more sustainable projects such as archives and object collections, copyrights, ownership, and privacy issues must be cleared out. We suggest contacting local archives, libraries, and other cultural institutions to secure the paperworks and long-term storage and preservation of the items.

Step 5: How to acknowledge the public contributions?

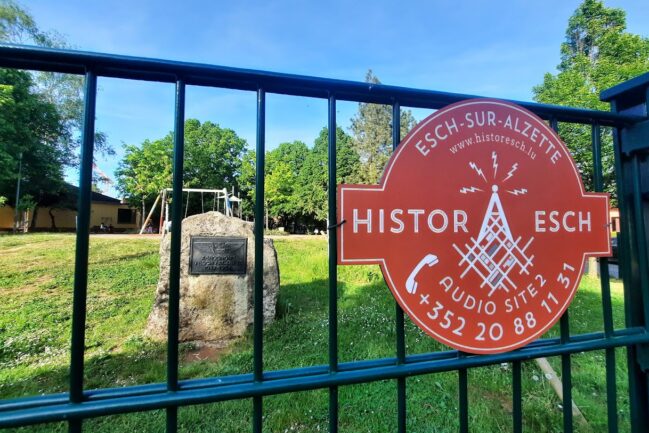

Every project needs to secure copyrights and permissions. Public participation requires additional safety nets as it often results in the use of unprocessed private photographs, documents and objects. Permission and clearances must be obtained from the concerned partners and participants. In addition to consent forms, project managers need to comply with legal and GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) terms. This includes not only the right to collect but also to display documents in a public framework. For instance, permission from the city architect was needed to hang our audio-tour sign (figure 5) in the public space.

When the moment arrives to launch the project publicly, you want to make sure that all the partners and contributors to the project are invited and acknowledged as participants. Organizing a launch event creates a moment of social gathering and allows for the media to promote your event to a broader audience.

Step 6: How to evaluate your project?

Before wrapping up a project, consider assessing your activities, the public participation, and its public interaction. You can evaluate the project by looking at the media’s coverage and the public comments. It is also useful to monitor the online level of engagement and interaction – especially if you use and develop parts of your projects through websites and social media platforms. Collecting surveys (perhaps even before and after the activities to compare the public’s understanding of the project and its reactions to the work presented) is also a customary measure.